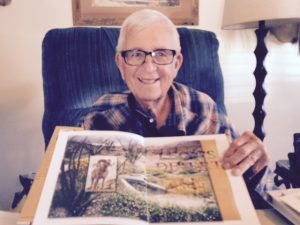

Brawley resident and Imperial Valley native Leon Lesicka is pictured with the book, Leon’s Desert, which was penned by former Congressman Duncan L. Hunter about Lesicka’s work as a conservationist in the Imperial Valley desert.

For more than 30 years the name Leon Lesicka has been associated with conservationism in the Imperial Valley desert from providing water holes that have allowed wildlife to thrive to maintaining a healthy environment and clean waterways.

And at age 84, the man former Congressman Duncan L. Hunter dubbed “America’s Greatest Conservationist” is not ready to slow down.

His current undertaking: the building of a ten-acre wetlands on the Alamo River in Holtville, a project funded through a recent $3 million federal grant administered by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, that will clean the water flowing through the river and ultimately improve the quality of drainage flows to the Salton Sea.

It is the latest wetlands project that Lesicka and his well-respected and award winning organization, Desert Wildlife Unlimited, have been a part of to provide both wetlands and clean the New and Alamo rivers as a means of creating a healthier Salton Sea. Two wetlands already exist on the New River—one west of Imperial and the other west of Brawley; a third was already built on the Alamo east of Brawley.

To call these projects and all Lesicka has done in the desert a passion of his would be an understatement. Referring to his efforts as a calling would be far more accurate.

Interviewed at his home in Brawley, with his wife of 66 years, LaVelle, close by, Lesicka humbly said of his life: “I have had a very interesting life.” The father of three and grandfather of six went on to say that he has put in drinkers to aid wildlife not only here in the Valley desert, but in Utah, Arizona, Mexico and even Mongolia.

His work in the desert began in 1980 when during the lining of the Coachella Canal, a 140 mile waterway through the Valley’s far eastern desert, he documented that as many as 179 deer mule died in the lined canal.

“I know we lost 179 deer that I know of personally,” he said. “When you lose 179 deer and you have a small herd, it bothers the heck out of you. It’s just not right.”

The deer were used to using the earthen canal. Lesicka, a longtime hunter who spent years in what he refers to as the rough desert, witnessed this, pulling deer out of the canal. He decided something had to be done. With the aid of others, those who would become the original members of Desert Wildlife Unlimited, they set out to build drinkers that would keep the deer out of the canal.

“Have you ever pulled a dead deer out of a canal and wondered if you could have kept them away and protected them? I had to do something,” Lesicka said.

While that moment in time may have started his work in the desert, Lesicka’s love for the outdoors, the environment and the Imperial Valley began long before that.

Lesicka is an Imperial Valley native. His father, Joseph Lesicka, immigrated to the United States from Poland at the age of 17 and moved to the Imperial Valley in 1928 where he raised hogs. Lesicka was born in 1932 in Holtville, the youngest of five brothers. Though born in Holtville, he was raised on land adjacent to the Salton Sea on land that would eventually be inundated by the rising sea.

Lesicka fondly looks back on a Depression Era childhood where his family didn’t have much money, but they had each other and a vast area in which to play.

“I spent quite a bit of time at the Salton Sea,” he mused. “The fishing was fantastic.”

He would go on to attend and graduate from Brawley Union High School and then pursue a career in construction—a career interrupted when he served two years in the Army, from 1952 to 1954, stationed in California. When he returned to the Valley, he continued his work, opening his own construction company.

All the while his love of hunting guided him into the rugged Imperial Valley eastern desert where he gained a respect not only for the wildlife he pursued but the environment that supported herds of mule deer, bighorn sheep and dozens of other species.

“I believe most hunters are conservationists,” Lesicka said. “In fact, I know they are.”

After the death of mule deer in the Coachella Canal, Lesicka joined by his friends and fellow Desert Wildlife Unlimited members, began their quest of building water holes of the wildlife first to keep them away from the canal but then to preserve wildlife throughout the desert.

According to a book about Lesicka, titled, Leon’s Desert, by his longtime friend, Duncan L. Hunter, Lesicka and his group built such watering holes over hundreds of square miles from the Chocolate Mountains in the Valley’s east desert to the Sand Tank Range of Arizona. Drawing on his construction knowledge, the drinkers he built were designed to self-replenish with the little rainfall that fell in the desert.

Lesicka is quick to point that it was a team effort. All of the work done came with the help of those in Desert Wildlife Unlimited, volunteers and with federal, state, local government and private funding.

“It’s not just me. It never was,” he said. “I get a lot of credit, but there are a lot of people who have worked their hind ends off. I just pushed them a bit. I just hope they appreciate what I pushed them into.”

The efforts of Lesicka and Desert Wildlife Unlimited have included building wetlands habitat along the Salton Sea for dove, which stands as an example today of what can be done with a little investment and ingenuity to establish wetland areas around the sea.

It was in 1997 that then Congressman Duncan L. Hunter approached Lesicka with the idea of building wetlands along the New and Alamo rivers to clean those tributaries, which ultimately feed into the sea. The New River had the dubious distinction as the nation’s most polluted river, in particular as the water flowed into the Valley from Mexicali.

Lesicka embraced the idea and the working relationship between Lesicka and Hunter led to the building of critical wetlands but the two also forged a longstanding friendship. The two remain friends today.

In his book, Hunter likens Lesicka to two other historical conservationists, President Theodore Roosevelt and Aldo Leopold, the father of wildlife conservation movement. Hunter writes of Lesicka: “Leon Lesicka’s conservation work, unlike Teddy Roosevelt’s park-creating legislation and Leopold’s inspirational writings, was accomplished with hard, physical labor. His ‘book pages’ were the sandy washes and mountains of the desert Southwest. His ‘writings” are a network of desert water sources brilliantly engineered to use nature’s infrequent rainstorms to catch and hold life-sustaining fluid.”

Today, Lesicka, who throughout his life has shunned politics, choosing instead to devote his life to the volunteer work of protecting this desert region, looks forward to breaking ground on the Holtville wetlands project. He is thankful for the federal funding that came around at the right time to make that project possible.

“It’s going to give Holtville a great park and it’s also going to clean the Alamo River,” he said. “The water quality element is the primary goal, but there are so many secondary goals. Everything about it is a plus.”

Current sitting Congressman Duncan D. Hunter, R-50th District, son of the elder Hunter, has advocated for the wetlands projects, including the Holtville project, just like his father. The younger Hunter said such efforts are meant to make a difference at the sea.

“Over the years, the New and Alamo rivers wetlands efforts are the only projects involving the Salton Sea and the two rivers that have consistently proven effective in terms of actually turning dirt, achieving results and involving the community,” he said.

Congressman Hunter added, “The federal support for these wetlands programs is critical for their continued success and I remain personally committed to provide any support required to ensure that Leon, Desert Wildlife Unlimited, and the Imperial Irrigation District can continue this important effort.”

He praised Lesicka for his work throughout the years. “Leon has been a great friend for many, many years. He is the gold standard of getting things done and his service and commitment to the projects with which he is involved epitomizes the true ‘let’s get to work’ character of the Valley.” “Over the years, the New River Wetlands effort is the only project involving the Salton Sea and New River that has consistently proven effective in terms of actually turning dirt, achieving results and involving the community. The federal support for this program is critical for its continued success and I remain personally committed to provide any support required to ensure that Leon, Desert Wildlife Unlimited, and the IID can continue this important effort.”

Lesicka’s work won’t end with the Holtville project. Recently, an illness left him sidelined for a time, but now that he is on the mend, he has begun to venture back out into the desert. It’s where he belongs. Where he is happiest.

His one hope, however, is that one day there will be others who will take his place in leading such efforts. He is confident there will be in be, in particular as Desert Wildlife Unlimited continues to play such an active role in the Imperial Valley.

“I just know there will be others who continue this work,” he said.