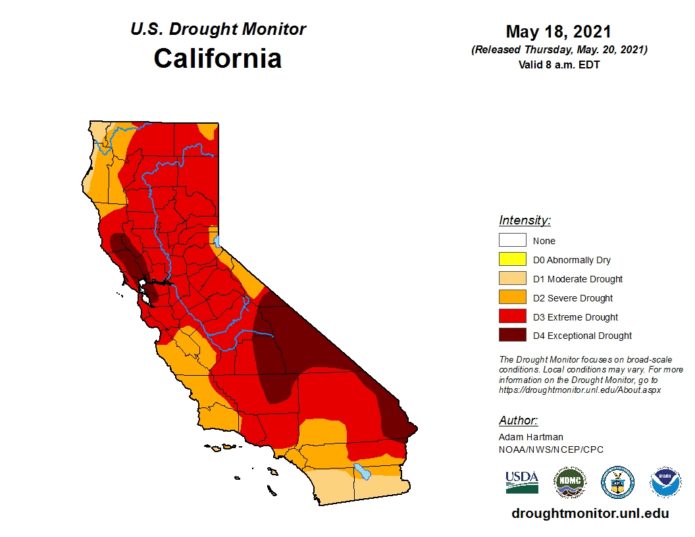

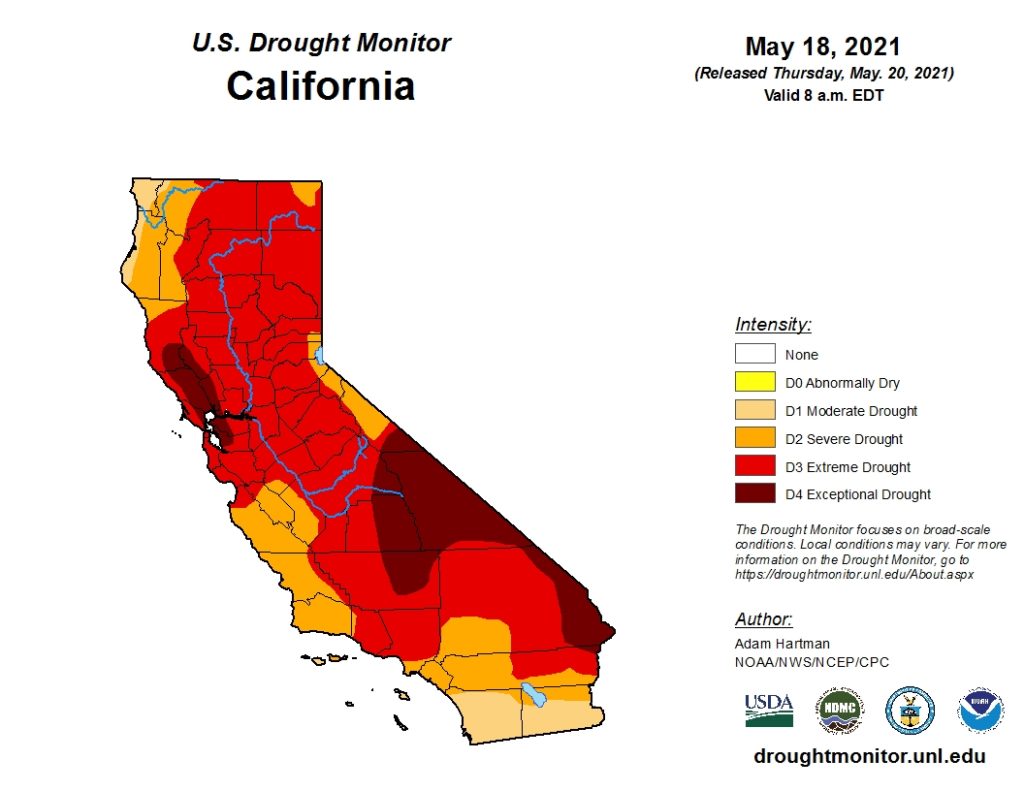

Anyone who pays attention to water issues—or has read about the most recent actions by Gov. Newsom to declare drought emergencies in much of California—knows we find ourselves in a prolonged and, for the most part, uncompromising drought. While in the last couple of years, snow and rain have pushed back a little, the same cannot be said for this year. What limited snowpack there has been, was swallowed by dry soils, which means any snows have done little this year to help the drought. On the Colorado River, in particular the Lower Basin, the most recent projections by the Bureau of Reclamation highlight a worsening situation and the likelihood of consecutive shortage declarations on the river in coming years.

The projections for the Lower Basin, of which California is a part, predict shortages on the river beginning in 2022 through at least 2025 as the level of Lake Mead slips below level 1,075 feet. That is the first target for a shortage declaration where the first formal shortage cutbacks totaling 383,000 acre-feet for Arizona, Nevada and Mexico are implemented. This is in addition to the 230,000 acre-feet of Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) contributions already agreed by those entities for a reductions in use of 613,000 acre-feet in 2022.

California does not face cutbacks under the three formal shortage triggers, which come when Lake Mead falls below level 1,075 feet, 1,050 feet, and 1,025 feet. However, California does face requirements under the DCP, adopted in 2019. Under the newest projections, the likelihood of the river reaching the second level of shortage cutbacks increases, especially in 2024 and 2025. Under that second level, the cuts to Arizona, Nevada and Mexico increase to over 700,000 acre-feet. Perhaps the most disheartening news from the latest projections is that there is an increased likelihood of Lake Mead reaching the DCP trigger at 1,045 feet—that requires the first California contributions of at least 200,00 acre-feet (a 36% chance in 2024 and a 38% percent chance in 2025). Note, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California is responsible for covering the majority of California’s share of the requirements, although Coachella Valley Water District and Palo Verde Irrigation District have also agreed to cover 15 percent of California’s share under the DCP agreements.

As we contemplate the meaning of these projections—and the impacts of the ongoing drought—there is much to discuss. Most importantly, is the need to work together on the river system to protect the river’s operations during these challenging times and for generations to come. Very important negotiations as to the future of river operations are upcoming with the goal of developing new operating guidelines for the management of the river that are to be adopted in 2026. There is no doubt those talks will be difficult among the Basin States as they balance their respective interests with the needs of protecting the river. To that end, it will be critical to find ways to align interests with the common goal of protecting California’s share of the river while ensuring the river continues to meet the needs of all stakeholders for generations to come.

The challenging conditions created by drought and the diminishing levels in Lake Mead also serve as a reminder of just how important conservation continues to be. Conservation isn’t just a sign of the times; conservation is going to continue to be key even as the river conditions may someday improve. Conservation—even under better conditions—will be essential to protect the river for today and future generations. Along those lines, the Quantification Settlement Agreement (QSA), which reduced California’s use of the Colorado River to its historic annual allotment of 4.4 million acre-feet, continues to be essential in helping to manage river supplies. The cornerstone of the QSA continues to be the conservation implemented by the Imperial Irrigation District and Imperial Valley farmers and funded by the San Diego County Water Authority as part of the nation’s largest agriculture to urban water transfer. That collaboration ensures that the QSA remains a testament to California taking a lead in conservation. The QSA also sends a message that California has and is continuing to do its part to conserve, and it shows what can be accomplished when agencies work together.

As we look at the next few years on the river and consider the future of river operations, there is no doubt tough times lie ahead. We know change is coming when it comes to the river. However, it is fair to say that change has already started. The Colorado River Basin States are taking steps to conserve and manage their supplies not only for their own needs but for the needs of the Colorado River. It is those steps that have gotten us this far in what has been a 20-year drought. Going forward, it will be critical that we find ways to work together, as generations past have done, toward a common goal of ensuring the Colorado River can continue to serve the needs of all stakeholders. We need to look forward to the better hydrologic years that will hopefully come, but we also need to continue down the path of preparing for the hard times—together.

There will be much more to discuss in the months and the years to come, and it will be essential for us all to stay vigilant. Consider this blog a place to share ideas and engage in a discussion on river matters.